Neon warrior Jenny Holzer on America today.

From school shootings to #MeToo and outrage at Trump, Jenny Holzer has spent her life battling injustice. As the Tate focuses on eight pivotal moments, the artist looks back at an eventful career

‘I hope my crummy old phone doesn’t make you crazy,” says Jenny Holzer as we begin our conversation. Not exactly what I’m expecting from the artist renowned for her pioneering use of technology. Holzer rose to prominence in 1982 when she reprogrammed an LED advertising billboard in Times Square with her own acerbicand sometimes conflicting messages (what she calls Truisms), such as: “Protect me from what I want” and “Abuse of power comes as no surprise.”

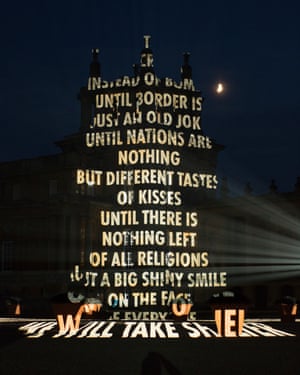

Over the course of her 40-year career Holzer has consistently employed some of the most advanced media and digital technologies in the production of her work, including: virtual reality, drones, projections, net art and, in her 2017 project at Blenheim Palace, robotic assemblies and an augmented reality mobile app.

A series of rooms dedicated to her work, opened recently at Tate Modern in London, pinpoints eight distinct points in her artistic career. It begins with a series of drawings Holzer made in 1976 when, she says, “I really didn’t know what I was doing, but I was getting serious about becoming an artist.” This exhibition transports the viewer to the present moment with IT IS GUNS: STUDENTS TALK SENSE 2018, a digital animation addressing US gun violence created especially for Tate. It was made as a direct response to the high school shooting in Parkland Florida in February, in which 17 students and staff members were killed.

Within two weeks of the attack, Holzer sent trucks to Florida, as well as to New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, Dallas and Washington DC, equipped with large LED billboards transmitting text such as: “STUDENTS WERE SHOT” and “THE PRESIDENT BACKS AWAY”. As the work’s title suggests, the project is to support the students’ Never Again MSD political action in the wake of the attacks. The trucks were parked at major city landmarks, including Trump towers in New York and Chicago, and were present at the March for Our Lives student protests in Washington DC, Chicago, and Atlanta on 20 March. On exhibition at Tate Modern is a newly created digital animation generated from footage and stills gathered at these locations and edited together with text that Holzer wrote as the events unfolded.

“I wanted to collect what we did very, very, quickly after the Parkland shooting,” she says. “Wanting to show the work at Tate made me assemble the stills and video, and go back into the animation. I wanted to be able to show the content to another group of people.”

Accessibility and consciousness-raising helped guide her choice of works at Tate Modern: “If I tilted the selection for this show, it would be towards pieces that have been outside, that have been for a general public,” she says.

Working on the street has been at the core of Holzer’s practice from the start and communicating with the broadest possible audience is still something she strives for. Now 68, Holzer began working in New York’s Lower East Side, alongside mural and graffiti artists such as Keith Haring, Lady Pink, A-One and sign writer Ilona Granet, with whom Holzer was part of a non-profit artists’ co-operative called Colab.

It was as a member of Colab that Holzer produced her first public project, a series of Truism street posters, a version of which can be seen in this exhibition. “Colab wanted to work outside of the art world proper,” explains Holzer, “to offer something that would be of some use or interest to others.” The artist credits the collective with introducing her to the benefits of collaboration: “That was the beginning for me, and it’s sustaining to work with others. It also makes up for the time when one is alone and miserable – that necessary time for art making, solitary art making.”

The exhibition features three large graffiti paintings from 1983-4 made with Lady Pink and Granet. In two of the paintings fiery apocalyptic scenes with figures burning on the New York subway are depicted. The phrase: “I am not free because I can be exploded anytime,” has been executed by Granet in a bold oversized font reminiscent of early computer games.

Sharing a stage with these lesser-known artists is indicative of Holzer’s ongoing commitment to advocating for women and prioritising their experiences. In a recent public conversation with Tate Modern director Frances Morris, Holzer discussed the importance of anonymity in her work and her early anxieties about succeeding as a young woman in an art world dominated by men: “Anonymity was key for me because I was unsure of myself and I also didn’t want the content to be rejected. I wanted people to focus on the art and not on the author.”

Despite a reluctance to become a public figure, Holzer has reached a colossal level of international recognition, a status arguably never afforded to any other contemporary female artist. Yet success and self-questioning seem to go hand in hand for Holzer. Commenting on her 1990 selection to represent America at the Venice Biennale she says: “It was nice because I was the first woman to represent the United States with a solo show, but that was part of the fear. If I am awful, I don’t want people to think it’s the ‘girl problem.’”

Graffiti paintings and hand-drawn sketches may not be what we first associate with Holzer, but they feature prominently in an exhibition that provides a surprisingly expansive image of her practice. “Rather than a complete retrospective, it’s moments of time in the process. I would call it process rather than progress,” she says. When I mention to Holzer how amazed I am to see the 60 or so hand-drawn diagrams that fill the glass vitrine in the exhibition’s entrance, detailing eye movement patterns and human memory function, she says: “They are obsessive. I don’t know how many hundreds of them I did, from ones about theoretical physics, to psychology, to medical things. They are distilled representations of things visual and all have captions that I faithfully transcribed.”

The drawings are products of Holzer’s time at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design where she began studying in 1975. She spent a large portion of the year in the library poring over books filled with such esoteric diagrams: “I was trying to makeup up for not really having an art education. Also, I was curious how people combined visuals and meaning. How one could represent content to people.”

While the Truisms were intentionally ambivalent and contradictory, her political message has become much more direct and unequivocal in recent years. When asked how she feels about what’s happening in America at the moment, she says: “Oh, aghast, demoralised, scared, disgusted, and a whole host of other things, it goes on … ” And regarding her work’s inclusion in London’s new US Embassy in Nine Elms south-west London, a building which Donald Trump condemned: “I’m happy to be any place he isn’t,” she replies.

Holzer’s earlier work has a tendency to find new resonances in the present moment of political unrest. Her Truism “abuse of power comes as no surprise” has been adopted by the We Are Not Surprised campaign group, an offshoot of the #MeToo movement seeking to expose the sexual harassment and misogyny rampant in the art world. The movement was sparked by multiple accusations of sexual misconduct levelled at Artforum publisher Knight Landesman last autumn. “I was glad people asked me if they could have it. I’m honoured,” Holzer says, before making a statement that could sum up her career: “Please take it, run with it, use it. There’s work to be done.”

• Artist’s Rooms: Jenny Holzer is at Tate Modern, London, until 31 July 2019.

The article appeared first in theguardian.com.