Susan Hiller, 78, Maker of Dreamlike Conceptual Art, Dies – The New York Times

Susan Hiller, 78, Maker of Dreamlike Conceptual Art, Dies

Feb. 1, 2019

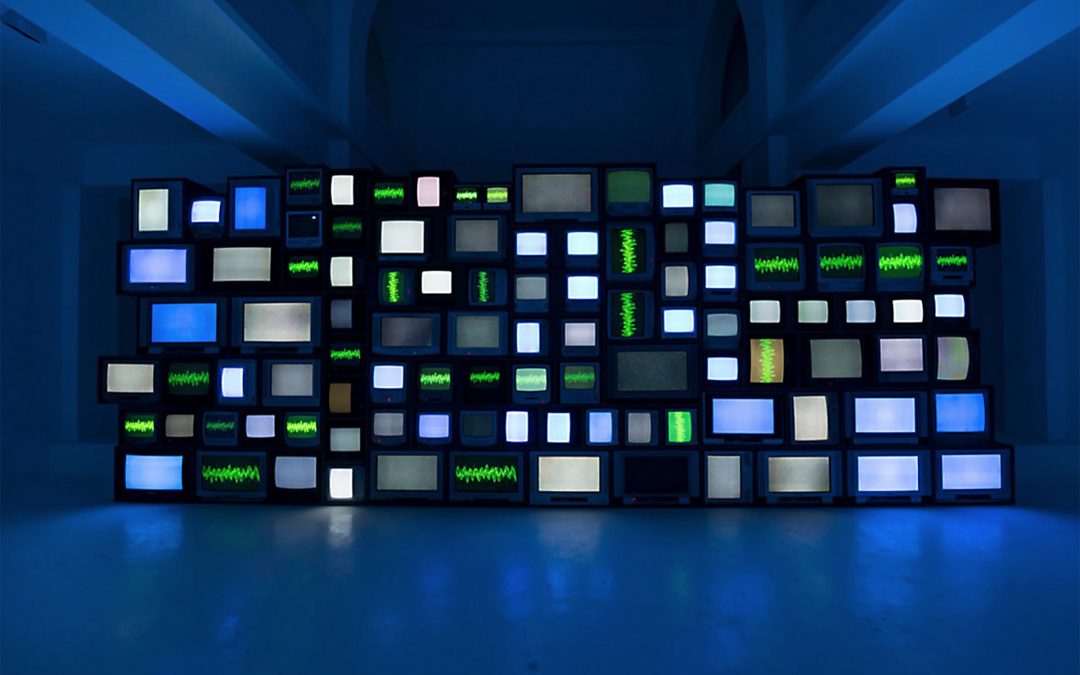

In Susan Hiller’s installation “Channels” (2013), disembodied voices come from a wall of more than 100 television sets and tell their stories of near- death experiences, with the sound of each voice visualized in the electronic patterns created by an oscilloscope.O.H. Dancy, via Lisson Gallery

In Susan Hillerʼs installation “Channels” (2013), disembodied voices come from a wall of more than 100 television sets and tell their stories of near-death experiences, with the sound of each voice visualized in the electronic patterns created by an oscilloscope.O.H. Dancy, via Lisson Gallery

Susan Hiller, a leading British conceptual artist whose video, audio and photographic installations ingeniously explored extinct languages, alien abductions, girls with psychic powers and the Holocaust, died on Monday in

London. She was 78.

Her son, Gabriel Coxhead, said the cause was pancreatic cancer.

Ms. Hiller’s mysterious and dreamlike art, which often made use of marginalized and forgotten artifacts of modern culture, played at the precipice between reality and the subconscious and often explored the paranormal.

“I consider that definitions of reality are always provisional, that we are all involved collectively in creating our notions of the ‘real,’ ” she said in an interview for the catalog to an exhibition of her work at the Site Gallery in Sheffield, England, in 1999.

Born in the United States and educated as an anthropologist, Ms. Hiller was particularly adept at using video to look anew at reality. One vivid (and frightening) example of her ability to manipulate moving images is “An Entertainment” (1990), a video installation that uses traditional Punch-and- Judy puppet shows to expose the violence to which children are routinely exposed.

The artist Susan Hiller in 2014. “I consider that definitions of reality are always provisional,” she once said, “that we are all involved collectively in creating our notions of the ‘real.’”Carla Borel, via Lisson Gallery

The artist Susan Hiller in 2014. “I consider that definitions of reality are always provisional,” she once said, “that we are all involved collectively in creating our notions of the ‘real.ʼ”Carla Borel, via Lisson Gallery

She and her son, Gabriel, traveled through England when he was still a teenager to film the puppet shows with a Super 8-millimeter camera. After intensifying its colors, magnifying its images and slowing down the action, she projected the grainy footage onto four giant screens that surrounded

viewers with the heightened brutality. The effect was to make those watching feel as if they were in a box.

“I went to many puppet shows when my son was growing up, and I’d hear the littlest children crying and wanting to leave, and their parents saying, ‘Oh, look at Mr. Punch, isn’t he funny?’ or ‘Don’t be silly, there’s nothing frightening here,’ ” Ms. Hiller said in an interview with Sculpture magazine in 2012. “I realized that denial is a ritual in our society — we’re training to deny our own experiences and laugh at our fears.”

In “The Last Silent Movie” (2007), she used a single screen to tell the story of dying languages through archived recordings of people speaking them and subtitles.

In “Psi Girls” (1999), a color-drenched work about the breadth of female imagination, she edited, slowed, tinted and enlarged scenes from five films (including “Firestarter,” “The Fury” and “Matilda”) featuring girls with telekinetic or psychokinetic powers. She added rhythmic handclaps and nonverbal gospel singing, and projected the work simultaneously onto five large screens.

“Psychokinesis is subject matter,” she said in an interview in 2018 with The Quietus, a British digital music and pop culture magazine. “It’s not the content of the work. Everyone wants to know if I believe in ‘this stuff’ because it perplexes them; I provide them with something that they don’t want to think about, although it’s all actually just special effects.”

At top is a detail from Ms. Hiller’s “10 Months” (1977-79), an arrangement of 10 black-and-white photographs, accompanied by excerpts from her journal, documenting her pregnancy. Below is the entire work.George Darrell, via Lisson Gallery

At top is a detail from Ms. Hillerʼs “10 Months” (1977-79), an arrangement of 10 black-and-white photographs,

accompanied by excerpts from her journal, documenting her pregnancy. Below is the entire work.George Darrell, via Lisson Gallery

There were no screens, only voices, in “Witness,” an eerie 2000 work in which people’s accounts of encounters with aliens and U.F.O.s — taken from newspapers and other media and read by actors — are related through hundreds of tiny speakers dangling from a ceiling in a darkened space. At one point the jumble of voices narrows to a single one that comes from all the speakers.

The critic Richard Dorment of The Telegraph called the installation “breathtakingly beautiful” when it was exhibited at the Tate Britain museum in London in 2011. “Hiller’s true subject was the human need to tell stories,” he wrote, “to hold a listener spellbound and in so doing to join hands with Homer or the Brothers Grimm.”

Susan Hiller was born on March 7, 1940, in Tallahassee, Fla., and grew up in Cleveland and Coral Gables, Fla. Her father, Paul, had pharmaceutical, construction and insurance businesses. Her mother, Florence (Ehrich) Hiller, was a psychometric tester, a job that involved measuring people’s skills, personality traits and knowledge.

“I always wanted to be an artist,” Ms. Hiller told The Guardian in 2015. “This was my fantasy as a child.”

A corner of her bedroom became her art studio, but she became discouraged by the lack of respect given to female artists. While in high school, she read a pamphlet by Margaret Mead that inspired her to become an anthropologist.

Sign up for Breaking News

Sign up to receive an email from The New York Times as soon as important news breaks around the world.

Ms. Hiller’s “After Duchamp” (2016-17), part of a series of homages to other

artists.Jack Hems, via Lisson Gallery

Ms. Hillerʼs “After Duchamp” (2016-17), part of a series of homages to other artists.Jack Hems, via Lisson Gallery

After graduating from Smith College in Massachusetts, she studied for her Ph.D. in anthropology at Tulane University in New Orleans and did fieldwork in Central America. But during a lecture on African art at Tulane, she was overwhelmed by the images in a slide show and decided to become an artist and not finish her doctorate.

“I felt art was, above all, irrational, mysterious, numinous: The images of African sculpture I was looking at stood as a sign for all this,” she wrote in the foreword to “The Myth of Primitivism: Perspectives on Art” (1991), an anthology that she compiled and edited.

She and her husband, David Coxhead, a British writer she had married in

1962, traveled to Europe, Asia and Africa before they settled in England in the early 1970s. There she began creating conceptual art that was less austere than what other conceptual artists were doing at the time.

One of her early works, “Dedicated to the Unknown Artists,” developed from 1972 to 1976, exemplified her career-long approach to using ephemera or overlooked materials in her art.

In 14 framed panels, she collected more than 300 postcards showing sea waves crashing onto British shores — her homage to the artists who painted the pictures. In spirit, it is linked to “Monument,” a work from 1980 and 1981, in which she photographed 41 memorial plaques to local heroes that she had found in a park in London. She arranged the photographs in a diamond shape on a gallery wall; in front of the photographs she placed a park bench with an audiocassette player that has Ms. Hiller speaking in a recording about heroism and memory.

Notable Deaths 2018: Arts and Styles

A memorial to those who lost their lives in 2018

Aug. 3, 2018

“You become part of the monument,” Gabriel Coxhead, her son, said in a telephone interview, “and you’re linked to all the other spectators.”

In addition to her son and her husband, Ms. Hiller is survived by a brother, Robert Hiller. She lived in London.

In 2002, Ms. Hiller was in Berlin when she was startled to see a sign for Judenstrasse — literally “Jews Street” — and wondered how many other paths, lanes and roads with similar names still existed in postwar Germany. After three years of travel, she found her answer: 303, among them Judendorf, Judenhof, Judenweg and Judgengasse. Some had been renamed during the Third Reich but had their names restored during denazification.

“Some of them were very ancient streets, going back to the Middle Ages; some still had Jews living on them when they were taken away by the Nazis,” she said in an interview at the Tate Liverpool museum in 2008 with its director at the time, Christoph Grunenberg.

She turned her findings into “The J Street Project,” which consists of a grid of all 303 photographs, a 67-minute film and a book that reflects on the Holocaust — without ever mentioning it specifically — through a succession of images of banal street images.

In reviewing “J Street” when it was shown at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco in 2009, Kenneth Baker of The San Francisco Chronicle wrote that “it demonstrates the capacity of a good idea to draw alarming cumulative power from ostensibly matter-of-fact material.”