Joseph Kosuth, the American conceptual artist has plenty of stories to tell – but when it comes to the meaning of art, he’s serious.

Joseph Kosuth was 24 in 1969 when he wrote his seminal essay, Art After Philosophy. It’s a staple of art theory classes everywhere these days, but when I ask him about it, he immediately reminds me how young he was back then.

“I threw a lot of things in and maybe not quite as thoughtfully as I could have,” he says.

At 72, the American conceptual artist is just as forthright and opinionated as he was when he was writing “agitprop art theory” as a self-described wunderkind – though now he is bolstered by more than 50 years of a high-profile artistic career.

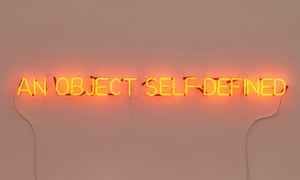

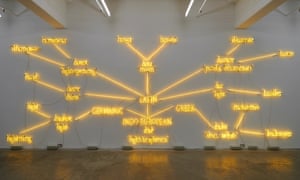

Frequently self-referential, concerned with language, philosophy and the nature of art itself, Kosuth’s works pioneered the use of text – of words, language – as visual art. One of the key figures in the conceptual art movement of the 1960s, who rejected a conventional understanding of art in favour of focusing on the ideas behind the work, he has maintained a career as a curator and writer as his pieces have been exhibited across the world, featuring in the permanent collections of major museums with career retrospectives travelling across Europe.

So Kosuth is reasonably surprised when, sitting on a metal stool at one end of a stark, whitewashed room covered in his works in Flinders Lane, Melbourne, I tell him that his art – which has not been seen much in Australia – is relatively new to me.

“Darling, how did you manage to avoid me all these years?” he exclaims.

Kosuth has a gruff manner – accentuated perhaps by the fact that he is slightly hard of hearing “this week” – but he is engaging and opinionated. He is known for having high-profile connections, and when conversation turns to politics, the anecdotes begin to flow.

There was the time actor Vanessa Redgrave would “pound on my door and sit in my kitchen and go on and on, trying to convince me to join her revolutionary workers’ party – oh mon dieu!” he says, putting his head in his hands.

Then there was his ancestor, Lajos Kossuth, who played a significant role in the Hungarian revolution of 1848, and who corresponded and ultimately fell out with Karl Marx. “And gave away some thousands of hectares! My inheritance! Gave away to the Hungarian people!” Kosuth laments. “Which is fine – I did fine without it, thank you very much.”

When it comes to art, though, he is serious: “Artists make meaning; that’s what we do,” he says. Kosuth’s own brand of meaning-making is most often represented by his most well-known work, One and Three Chairs (1965), in which a chair, a photograph of that chair, and the dictionary definition of the word “chair” are installed side-by-side.

A Short History of My Thought, currently on show for Melbourne festival at Anna Schwartz Gallery, is perhaps the ideal entry point for a Kosuth novice. Comprising mainly neon, language-focused pieces made between the mid-1960s and a couple of years ago, the exhibition is less a retrospective than a judicious sampling of a career built on questioning the very nature of art itself.

Kosuth initially supported his art practice with teaching, until it began to make enough money to sustain itself. But younger artists, he says, seem to be particularly influenced by commercialisation, unconsciously conflating artistic worth with financial value. He is scathing of those who are “stupid enough” to think that the answer to “who is the most expensive?” can also answer the question “who is the best?”

“Those artists at the top of the list of billionaires’ [collections] are rather quite derivative artists,” he says. Then: “They’re friends of mine, so I won’t say specific ones. But I watch this phenomenon and they cite me as their childhood hero sometimes and I don’t know what to do with that.”

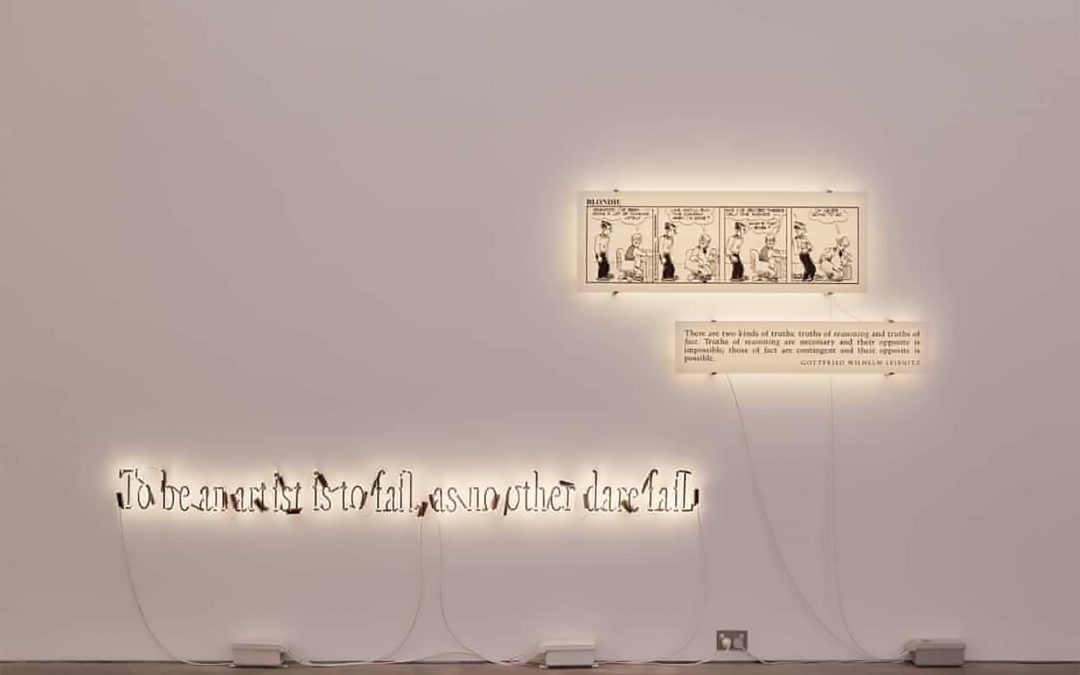

By way of explaining how stifling commercial considerations can be to art, he points across the room to where Double Reading #12 is hanging – a work comprised of a Blondie cartoon and a quote from the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz about the nature of truth.

“This was a show I did in LA at Margo Leavin [Gallery]. It was a really long time ago, and traffic was terrible that night in LA and I got to my opening like, in the middle of it, and as I walked in these Hollywood lawyers that were collectors of mine came running out, saying, ‘Joseph, did you get permission to use that [cartoon]?!’ I said, ‘No’.”

He notes that he didn’t get permission from Leibniz either, but permission was not the point. “I pointed to the Blondie cartoon and said, ‘See that? That’s not my work.’” He points to the Leibniz quote: “Not my work either. My work is the gap between. It’s where the surplus meaning is created from those two. Those are just props to give me that.”

This concern for spaces – for “the gap between” – is part of what drew him to use neon as a material in his art. “I needed something with qualities that I could unpack and separate,” he says.

“People were used to seeing [neon], although for other purposes than art. They were used to seeing these things lit on the wall. So I transformed them,” he says. “Any neon used before me was basically decorative, formalistic stuff.”

The concern for spaces also fuels his relationship with his audience. “I expect the audience to complete the work,” he says. “I am initiating a conversation. While I can explain my work and can talk about it, I am sometimes reticent to do it, because people want to look at the answers in the back of the book instead of working it out themselves.”

There are facts, however, that underpin his art – facts that are sometimes useful to know in order for the piece to resonate. Kosuth points to a large, pink work at the end of the gallery.

“That’s the very last word that [philosopher Ludwig] Wittgenstein wrote as he died,” he explains. “That was the word ‘language’, in German, crossed off. I mean, I was fascinated by that … it gives a human side that you don’t always get from dear Ludwig.”

I tell Kosuth I once studied that great thinker’s philosophies on language, and he nods approvingly. Kosuth curated the centennial exhibition in Wittgenstein’s honour for the city of Vienna – “the philosophers were fighting over his body – it’s very contentious, the Wittgenstein industry,” he says. He was also invited to create a work for the side of the house Wittgenstein made for his sister, Margaret.

Given his concerns about commercialisation, how should artists respond to the contemporary political moment?

“There are things you can do – ‘dirty tricks’ they would call it during the Nixon era,” he says. Kosuth was himself active against the Vietnam War, engaging in guerrilla-type creative activity like dropping little cards from a plane over Boston that said: “if this was napalm, you’d be burning”. “But it’s one thing to do that; it’s another to make it part of your career portfolio.”

Politics is always local, he says. “We have the worst president in memory and the thing about the American president is that he’s everybody’s president, he impacts everybody’s life, whether you have the opportunity to vote for the guy or not … but there are always local issues that have to be dealt with.”

Ultimately, though, it’s the role of artists to look beyond politics – beyond the temporary.

“We’re in a world where the two most powerful groups – the two motors of society – are on one hand businessmen and women who want to see profit at the end of the day, and on the other politicians, who want to maintain their power. Those are short-term goals, and if there’s a commitment only to short-term goals, it’s not good for society.

“That’s why the intellectuals, the artists, the writers – the intellectual workers, shall we call them – are so important. They provide the long threads in this textile of society.”

The article appeared originally in theguardian.com.